MODULE 2: Robber Barons, Refugees and Rebellions

The Statue of Liberty (1886)

The narrative put forward by the textbooks, media, etc. about the US is that it’s a “society of immigrants.” These migrants came because they were “seeking a better life” or they wanted to pursue “the American Dream.”

While there have surely always been such adventurers in the world, this type of migrant represents a tiny minority of the total. What would much more accurately describe the vast majority of those who crossed the Atlantic or the Pacific oceans headed for the US is refugees. Most of the rest were slaves, brought by force from Africa, or British subjects being punished by deportation to the colonies, in the early days of settlement.

This “society of immigrants” was always very much divided by class and race, among other things. The immigration policy was explicitly whites-only for most of the country’s existence. People of color from places like Mexico could freely enter (until recent decades), but they were rarely treated like citizens, or given citizenship (unless they were born in the US and could prove it), while others (Chinese, Japanese) could be imprisoned or deported at any time, even generations later (in Canada, too).

And whether Chinese, Japanese, Mexican, Italian, Irish or Russian, the people that got on those boats headed for New York or San Francisco were, primarily, refugees. That is, they were people desperately fleeing war, despotism, famine, and other types of calamities. And for most of them, what awaited them in the US was more of the same.

In recent years, the question of who deserves to pursue this “American Dream” has been an especially contentious issue. Increasing numbers of people each year from Bush to Obama to Trump have been getting deported back to war zones in Latin America and elsewhere. War zones that were, not coincidentally, turned into war zones as a consequence of US foreign policy in places like Mexico, Guatemala, El Salvador and Honduras. For so many of these would-be migrants, there is no welcoming of “huddled masses yearning to be free” – there are only US-sponsored death squads awaiting them when they return home.

“Statue in the Harbor”

Age of the Robber Barons (1870’s-1890’s)

Early 21st-century US society is so dramatically unequal that you have to go back well over a century, to what has become known as the Gilded Age or the Age of the Robber Barons, to find a point in history when things were more unequal than they are today. But what about the Great Depression in the 1930’s? Wasn’t society extremely unequal during that period? Well, yes, it was. But now it’s worse.

For anyone struggling to contend with the housing market as either renters or potential home-buyers in the modern age (at least in an area where there are many jobs to be found), the scene during the Gilded Age would strike familiar chords. Because of overly-intimate connections between very rich industrialists and very rich politicians, the industrialists were being given vast amounts of prime real estate, which they were then selling at great profit – or keeping property off the market until they knew they could sell it at a big profit. That is, the government was giving away the country to real estate speculators and developers, who were then finding ways to use their property to make lots of money, which they were able to make mainly because of the fact that they owned all this property to begin with.

Faced with this more extreme version of the familiar reality that in order to find land you could possibly afford to live in you had little choice but to move further west, the millions of half-starving “American pioneers” did what they had to do to survive, at least until they died, usually at a relatively young age, from overwork, blacklung, malnutrition, etc.

A realistic depiction of this period of US history is important to counter the narrative that dominates in the elementary schools throughout the western states, which elevates “the pioneers” to mythic status. While moving long distances with horses and wagons and setting up a new life far away from home is certainly an impressive accomplishment, it’s vital to bear in mind that the vast majority of these people were desperately seeking a way to survive by settling in lands not yet controlled by real estate speculators.

“Age of the Robber Barons”

Boxcar Betty (1905)

After decades of corrupt and brutal rule by robber baron in so much of the US, the working class began to organize in powerful and ingenious new ways. In 1905 the Industrial Workers of the World had their founding convention. The union quickly grew to become the biggest, most militant union in the history of the United States (and it played a significant role in other countries as well, such as Canada, Mexico and Australia).

Before the IWW, labor unions in the US were generally focused on organizing workers within a certain trade. The IWW was all about organizing the entire working class, with a blatantly “class war” kind of orientation. They weren’t looking for compromises with the owners of industry – in that way, the IWW wasn’t a typical union at all, the way most of the world thinks of unions today. They were looking to take over – with strikes, sabotage, street protests, riot squads, newspapers and other tactics being ways to build towards victory, rather than just trying to win higher wages and better working conditions (which they also were trying to achieve).

But what distinguished the IWW from previous unions went far beyond their class war approach to organizing. They broke every other available mold, as well. They welcomed immigrants, people of color, and women into the union, at every level. Many of the union’s most well-known leaders and visionaries – Mary “Mother” Jones, Elizabeth “Gurley” Flynn, Emma Goldman – were women.

And these organizers were also distinguished from much of the labor movement before and since that period in that they weren’t living high on the hog off of the dues of their membership. The organizers themselves had to hop freight trains to get from place to place, just like the itinerant workers in mines, logging camps, and factories that they were working with. They were the first to use many tactics later associated with the unions of the 1930’s and the later Civil Rights movement, such as the sit-down strike, and packing prisons. And their favorite form of communication was art – songs, cartoons, poems, images.

Despite the massive numbers, pioneering tactics, and huge influence the IWW had throughout the US in the early twentieth century, it has been completely written out of most history books. The overwhelming majority of people who grow up in the US never hear a single word about the IWW throughout their education. It almost seems that the extent to which it has been ignored is equal to the extent to which it impacted the country.

“Boxcar Betty”

Joe Hill (1915)

From the beginning, repression against the radical labor movement in the US in the early twentieth century was intense. Vigilantes hanged union organizers under bridges, fired into tent encampments, left organizers in the hot desert to die of thirst. During the 1914 Free Speech campaign on the west coast, thousands were beaten and arrested by police for standing on the sidewalk and speaking out against the capitalists.

1915 was the year when the man who has gone down in history as probably the most well-known IWW organizer was executed by firing squad in the state of Utah. Joe Hill, born Joel Emanuel Hagglund and raised north of Stockholm, in the Swedish town of Gavle, emigrated to the US with his brother. He soon became the most well-known cartoonist and songwriter of the labor movement of his day – the most familiar example of the IWW organizing strategy of using simple, artistically-presented concepts and simple language to communicate important ideas about solidarity, and to teach lessons about how to avoid the various traps that the bosses will try to set up to prevent workers from successfully organizing.

There was not only constant state repression against the IWW, and state-sanctioned repression from private actors such as the Pinkertons, but authorities at all levels of government constantly used the courts to accuse IWW members of any number of offenses. Often they would be found not guilty, but the union would be drained of scarce resources in the process of fighting these charges, which was the point. And then oftentimes, the justice system being the way it is, the charges would stick – as was the case with Joe Hill.

The only evidence against him was that he was shot and injured by someone in Salt Lake City on the same night as a storekeeper was also shot and killed. Joe didn’t want to talk about the circumstances of his shooting because doing so would have probably ruined the life of the woman with whom he was having an affair. But under our “innocent until proven guilty” system of justice, he shouldn’t have needed to explain how it was that he didn’t shoot the shopkeeper. Nevertheless, he was found guilty and sentenced to death. Such was the contempt held for the IWW at the time in Utah that the governor ordered the execution despite the attempted intervention of the President Wilson.

The Irish Spring (1916)

The Easter Rising in Ireland against British rule was a seismic event that clearly happened at a certain time and place. It occurred as Irish subjects of the British Crown were dying in the fields of Flanders, during the “Great War” to which they were drafted. And it occurred at a time of growing radicalism in the labor movement in many countries, most definitely including both Ireland and the United States.

Why mention the US in the context of this Irish rebellion? Because, for one thing, two of its most prominent leaders, James Connolly and James Larkin, were as well-known as IWW organizers in the US as they were as leaders of the independence movement in their native Irish land.

The uprising in Ireland wasn’t just about national sovereignty in the face of centuries of brutal subjugation. It was also a movement for the rights of workers, a movement with a strong socialist orientation.

The Easter Rising did not militarily defeat the British, but it was the straw that broke the camel’s back after centuries of periodic anti-colonial uprisings and an ongoing guerrilla campaign against British rule. A few years after the Rising, 26 of Ireland’s 32 counties gained independence.

“The Irish Spring”

The Working Class Union (1917)

As much as the IWW has been written out of most of the history books, other organizations were far more obscure. The history of the working class is full of secret organizations – which were especially common in the days when organizing a union itself was a very illegal act. By 1917, although unions were legal, one could easily be forgiven for assuming they were not, since most any union member who exercised their rights to speak, assemble, or otherwise conduct union business was liable to be harassed, arrested, beaten, charged with a crime, or even killed.

The IWW had rules for who was eligible to join their union. Unlike other unions, being white and male was not one of those requirements. But not having employees was mandatory for members – so tenant farmers were not eligible, since even a relatively poor, exploited tenant farmer still had to employ seasonal workers during harvest time. So, barred from joining the IWW, in Oklahoma they formed their own organization – the secret Working Class Union.

Like the IWW, the WCU in Oklahoma enthusiastically drew from all sectors of local society, and included women, men, white, Black, and indigenous members. Unlike the IWW, the WCU’s main tactics involved industrial sabotage and campaigns of intimidation directed at those who owned the land on which they eeked out their living.

The years during which this 35,000-member organization conducted their activities might have been entirely lost to history, except for the group’s decision in 1917 to launch an armed uprising against the US government. In retrospect, the idea perhaps seems outrageous. But at the time, tens of millions of people were being slaughtered in an unprecedented global carnage known as the First World War, the biggest country in the world (Russia) was in the throes of revolution — and the US had just entered the war (after Wilson won the presidency on a campaign based around staying out of the conflict) and instituted the military draft. These Oklahoma sharecroppers decided that if they were going to be drafted and killed to fight in a war they didn’t believe in anyway, they might as well die fighting in a revolution against the landlords in Washington, DC.

Led, among others, by the descendant of one of John Brown’s chief lieutenants from the nearby state of Kansas, the revolution was quickly aborted when the would-be revolutionaries were confronted by a large posse of people from their own locality, who they knew well. Rather than fighting them, they surrendered.

Whether they would have gathered more forces as they marched from Oklahoma to Washington, DC will never be known. But if what has come to be known as the Green Corn Rebellion ever receives a mention by historians, the rebels are usually depicted as deluded and ignorant. However, if you put the rebels in the historical context in which they belong, I think you have to draw the conclusion that they were neither of these things.

“Oklahoma, 1917”

Neither King Nor Kaiser (1917)

Throughout the world there was widespread opposition to World War I. Labor unions and other social movements were broadly opposed to what they called a “bosses’ war.” Irish independence leader and IWW leader James Connolly also led the opposition to this bosses’ war among the Irish public. Variations of his quote, “we shall fight for neither king nor kaiser, but for Ireland” spread to other parts of the globe, including Scotland, where 1917’s Red Clydeside rebellion adopted the slogan, “a bayonet is a weapon with a working man at either end.”

Many mainstream accounts of the First World War cannot avoid depicting, at least to a limited extent, the unbearable slaughter involved, and the unprecedented scale and mechanization of the carnage. When it comes to a realistic presentation of the scale and breadth of the opposition to the war around the world, historical accounts are far less forthcoming.

The war was incredibly unpopular, and resistance was everywhere. In the US, Australia and elsewhere, governments essentially had to suspend democratic processes and impose martial law – charging dissidents with sedition and jailing them for their opposition to the war – in order to maintain the war effort. In Russia, the revolution of 1917 was in large part fueled by opposition to the Czar’s war against Germany, while in Germany, opposition to the war against Russia created the political environment that almost allowed a socialist revolution to succeed soon after the Russians overthrew their own authoritarian government.

“Neither King Nor Kaiser”

Ginger Goodwin (1918)

The young Ginger Goodwin left Yorkshire, England, where the average man worked in mines and died young as a result of the dangerous, unhealthy work and atrocious working and living conditions of the miners there at that time. Like so many other Europeans of the early twentieth century, Ginger left, hoping for a less brutal life in North America.

He emigrated to Canada, worked his way from east to west, and found that life there was just as brutal as it had been in Yorkshire. Like so many others in exactly the same boat, Ginger Goodwin joined the radical labor movement, becoming a well-known union leader on Vancouver Island in British Columbia.

Ginger, along with most of the Canadian labor movement and population in general, opposed the First World War. Almost exactly half of Canadian men failed medical exams and were exempted from military service. How much this says about Canadian men not wanting to be drafted, and how much it says about the general level of ill health among young Canadian men, is anybody’s guess.

What is not a matter of guesswork is that Ginger Goodwin already had blacklung from working in mines for much of his adult life. But, being a prominent union organizer, he did not get a medical exemption.

To avoid the draft, he hid out in the mountains, but a police officer hunted him down and shot him. When word got out about his death, the city of Victoria went on strike.

“Song for Ginger Goodwin”

The Palmer Raids (1919)

The FBI formed in 1908, but it was several years later when it was seriously funded by Congress and became the national police force that it is today. And like any national police force, it does the bidding of the federal government. By the time of the Palmer Raids of 1919, the federal government had decided that the radical labor movement needed to be destroyed.

Dubbing the IWW a criminal organization for being “German agents” (enemies of the bosses’ war were all “German agents”) the FBI rounded up 20,000 immigrant workers, ultimately deporting 6,000 of them back to war-torn Europe for the crime of being labor activists. They rounded up most of the leadership of the IWW, except for several who escaped to Russia, and jailed them. And they had a rightwing veterans group, the American Legion, burn down the union halls of the IWW systematically throughout the country.

The IWW continued to be a force in society for some years afterwards, but the FBI’s new, national, protracted war against the union made their long-term prospects as a major force impossible. Wobblies mostly drifted into other organizations, if they continued to be active in any. As for the FBI, they moved on to destroying other organizations and social movements – occasionally even targeting actual criminal organizations such as the mafia.

“Ballad of a Wobbly”

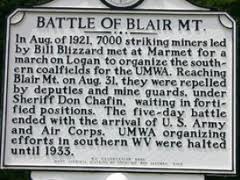

Battle of Blair Mountain (1921)

The biggest armed confrontation between two sides in the labor wars throughout US history was the Battle of Blair Mountain, more or less the culmination of what were known as the Coal Mine Wars of the period.

A hundred union miners were being held in a jail in the town of Mingo for being union miners, which naturally outraged the rest of the union miners in West Virginia. And then there were women and children massacred in the town of Sharples.

Thousands of miners and others marched toward Mingo from all over the mining state of West Virginia. Miners commandeered trains and other vehicles, and they emptied any stores of guns and ammunition they could find. Most were veterans of World War I, as were most members of the army that was assembling in Mingo to defend the town from the expected assault.

Much-loved IWW leaders such as Mary “Mother” Jones came to West Virginia and beseeched the miners to abandon their armed march on Mingo, fearing that people would be killed, and nothing would be accomplished. Before the massacre in Sharples, many people listened to her and turned around. But after the massacre, they headed back in the direction of Mingo.

Every cop in the state of West Virginia was in Mingo, along with various scabs and lawyers and anybody else that could be found who was against the miners having any control over their own lives. Ultimately assembled on either side of a densely-forested valley were many thousands of people, armed.

For three days and nights they fired at each other. Among the ranks of the union miners, well-organized contingents of women tended to the wounded, cooked meals, and did other things necessary to care for an army.

Because of the dense vegetation and the fact that neither side ever actually ran at the front lines of the other side – having seen first-hand the carnage that results from such tactics in Flanders. The number of people killed was relatively low, considering the amount of ammunition expended – thought to be fewer than twenty.

The Mine Workers Union didn’t receive widespread recognition until a decade later. In the efforts of the authorities to punish those who organized the rebellion, the law was changed to allow the miners to be prosecuted in a county different from the one where the alleged offenses occurred. But even with this new law, not a single jury anywhere in the state of West Virginia would convict the miners of anything.

“Battle of Blair Mountain”

Questions/thoughts for further exploration…

Statue in the Harbor (1886)

Was the US ever a “land of immigrants seeking a better life” or was it really mainly a country of refugees, slaves and displaced indigenous people? Who was really welcomed?

Age of the Robber Barons (1870’s-1890’s)

The history books talk about the brave pioneers. Who were these pioneers and why were they risking their lives to cross the country? What were they running from?

Boxcar Betty (1905)

Long before women could vote or Black and white people could swim in the same swimming pools, the IWW was led by women and people of color.

Joe Hill (1915)

The authorities were constantly charging IWW members with crimes they didn’t commit. In Joe Hill’s case, the charges stuck.

Irish Spring (1916)

Ireland was the first British colony. Most of the worst atrocities committed by British colonialism were first committed there.

Oklahoma, 1917 (1917)

The Green Corn Rebellion is generally depicted as a ridiculous little affair. But the Working Class Union was a significant organization that accomplished a lot in its time.

Neither King Nor Kaiser (1917)

World War I was globally unpopular, and widely opposed everywhere. In the US there was the Sedition Act…

Ginger Goodwin (1918)

Half of Canadian draft-age men got medical exemptions during World War I. What does this say about the health of Canadians at the time? What does it say about the popularity of the draft and/or the war?

Palmer Raids (1919)

The FBI is a national police force, and it was formed for the purpose of destroying the radical labor movement.

Battle of Blair Mountain (1921)

A pitched battle involving over 10,000 people on each side of a valley firing at each other for three days and nights.